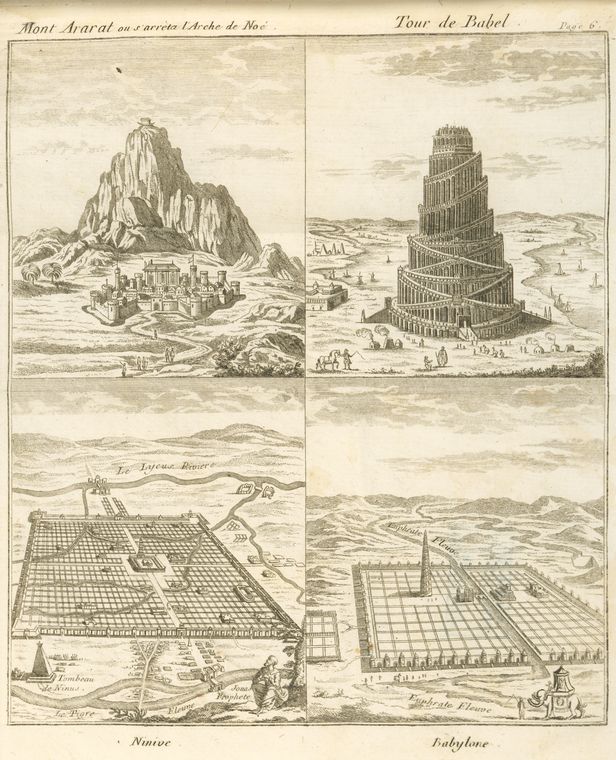

What does the Tower of Babel have to teach us about standing on the margin looking “in” on Christianity?

Over the last posts, we have seen how the dispersal of people into distinct language groups as God’s punishment remains a popular interpretation of the story. We come to question this, suggesting there is a different kind of meaning that can help us see ourselves and our very divergent religious tradition from a new perspective.

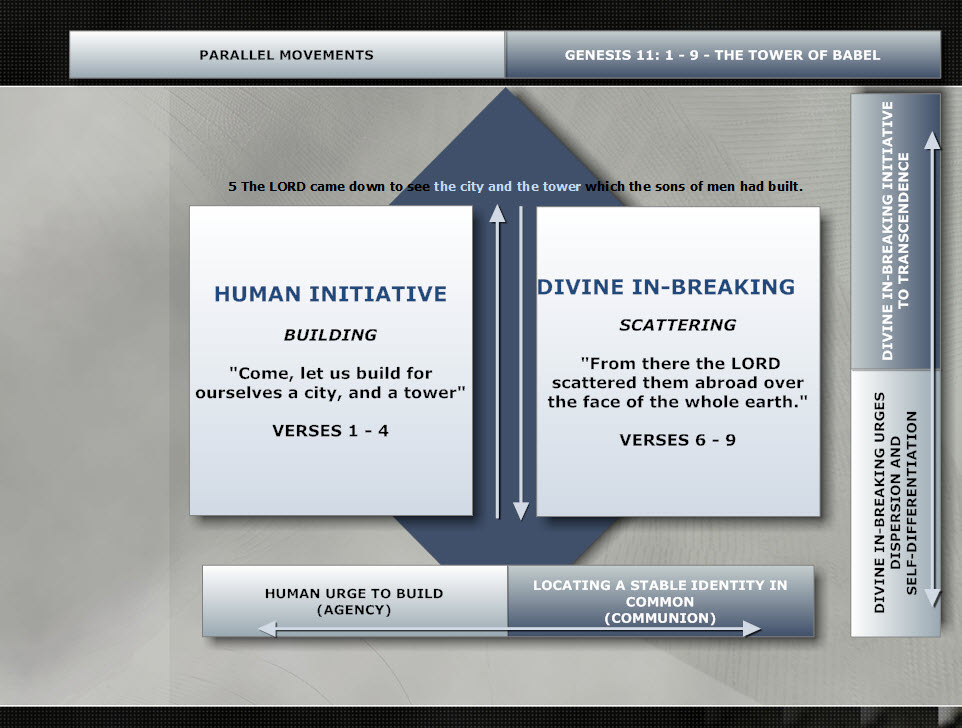

Inspired by biblical scholar Theodore Hiebert’s (2007) conception of Babel as a parallel movement of two opposing forces, we have seen that:

- Verses 1 – 4 describe what people naturally do: join together, uniting individuals through a secure, common identity.

- Verses 5 – 9 describe the divine response of scattering people away from that comfort zone

The story unfolds first as a metaphorical explanation of the world’s diversity of cultures, suddenly separated by linguistic incomprehensibility and geographical distance. Secondly, God intervenes in humanity’s tendency to remain stably anchored in its own comfort zone of identity, whether ethnic, linguistic, or geographical. God’s in-breaking initiative, wherein multicultural dispersion and ethnolinguistic multiplicity move people away from the center.

That is just the movement urged by Pope Francis:

Truly to understand reality we need to move away from the central position of calmness and peacefulness and direct ourselves to the peripheral areas. Being at the periphery helps to see and to understand better, to analyze reality more correctly, to shun centralism and ideological approaches.

It is not a good strategy to be at the center of a sphere. To understand we ought to move around, to see reality from various viewpoints. (Spardaro, 2014, p. 4)

Babel’s “two parallel halves” (Hiebert, 2007, p. 33) demonstrate the attempt to secure a community of mutual understanding so desired by Babel’s builders and its parallel divine antithesis, a complete undoing of the comfortable unity the city and tower provide.

Hiebert describes this inherent tension:

Attributing difference, that is, the extravagant array of the world’s cultures, to God’s intentions may simply represent a belief on the part of the storyteller that God as creator brought everything in the world he [sic] knew into existence, including its profusion of cultures. But it may also represent an understanding of the depth of the human need for identity and cultural solidarity, so that, left to themselves, humans—in this case, the family and their descendants who survived the flood—would dedicate their efforts to preserving a common culture. How in a world in which membership in a kinship group with a common culture defined human life in all respects, and outside of which an individual had no standing, could difference ever emerge? In such a world, cultural difference may have been considered possible only as part of a larger divine design, a design implemented by God’s own initiative. (2007, p. 57)

Herein lays the salient applicability of this succinct tale.

God’s intervention helps us step to the margin. The leap from kindred comfortability to the disruption of imposed difference takes us beyond the sameness of the center.

To move toward the unfamiliarity of the periphery is to move toward what is so “other” it is ultimately, inexplicably and mysteriously divine.

So what will see from out there, teetering on the apparent brink of unfamiliarity?

_____________________

References

Hiebert, T. (2007). The tower of Babel and the origin of the world’s cultures. Journal of Biblical Literature, 126(1), 29-58.

Spardaro, A. (2014). Wake up the world: Conversation with Pope Francis about the religious life. La Civilta Cattolica (I), 3-17.