The story of the Tower of Babel is an important key to stepping outward into the margin where we can see “inside” ourselves.

We previously noted how traditional interpretations of the dispersion of people after Babel (Genesis 11: 1-9) have labeled the event as God’s punishment. We also noted the difficulty of this interpretation since this presupposes the imposed differences to be undesirable, suggesting a divine preference for sameness and homogeneity that lacks evidence in the very diverse acts of creation elaborated earlier in Genesis.

Additionally, judgment upon folks coming together to build the story’s tower curiously appears in opposition to the natural drive for cultural solidarity, identity and belonging that has often contributed to human safety and preservation. Why would following this natural inclination incur divine wrath and retribution?

A Simple Gift

More questions arise as some interpreters take the scattering as a profoundly positive—rather than punitive—occasion for greater interpersonal growth. For one theologian, dispersion provides a space for “subtle and sensitive conversations, to the plurality of meanings, to nuances, poetry, creativity, and individuality” (Moyaert, 2009, p. 230) yielding authentic, self-transcending, and hospitable dialogue even across imposing barriers.

True as this may be, if you’ve ever read the rest of Genesis, that does not seem to be what happened to these folks (or to many of us when we are suddenly surrounded by a strange crowd). Rather than spaciousness, human beings seem more fundamentally to experience foreignness as a threat. Think about how you guard your valuables on a crowded subway!

We might see this story differently if we move outside of traditional or idealized interpretations. Beyond divine punishment or cultural opportunity, there is something very fundamental here we can easily miss. This simple idea can make all the difference in our ability to flourish and grow.

Dispersion to the Margins

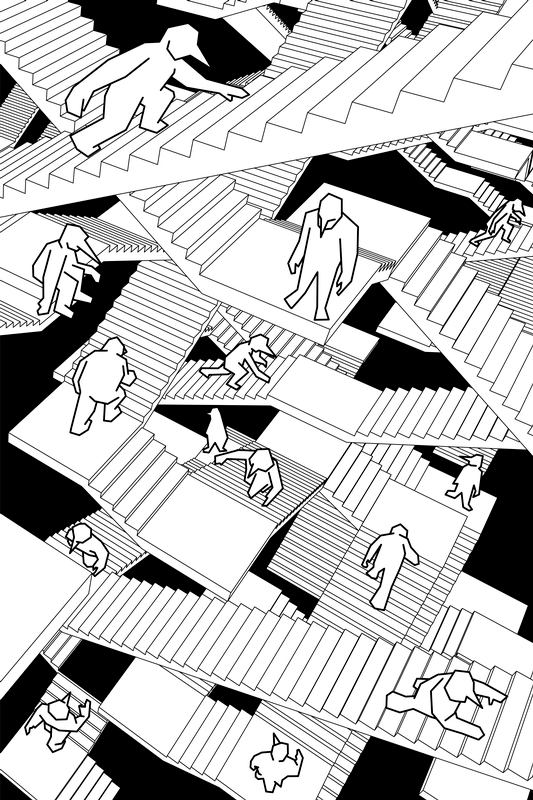

Essentially, building this kind of metaphorical tower is a natural human experience. We come together with others to create things that cement our collective identity, and that give us a name and a place. Realizing this inclination as part of our human nature, God’s intervention results from humanity’s natural desire to find identity and solidarity with other people. In this light, the divine act of dispersion simply moves the tower builders away from their comfort zones.

The scattering moves a unified “us” to a far-reaching multitude of very diverse “others.”

Rather than judgment inveighed against Babel’s builders, verses 1 – 4 of the story describe what people naturally do: join together, uniting individuals through a common identity. This fundamental perspective provides a critical clue to understanding the divine response of scattered dispersion in verses 5 – 9.

Dispersion, rather than punishment, sends us to the margin where we can begin to step outward to more fully see ourselves and our religious and spiritual traditions. As such, this well known Hebrew story suggests the need not only for the solidarity of cohesive identities, but focuses us on stepping out into divergent uncertainty. From this scattering, we are gathered to our commonly held, multilingual otherness.

What might being on the periphery mean for you?

What do you see when you look in on yourself, your spirituality, or your religious tradition?

References

Hiebert, T. (2007). The tower of Babel and the origin of the world’s cultures. Journal of Biblical Literature, 126(1), 29-58.

Moyaert, M. (2009). A “Babelish” world (Genesis 11:1-9) and its challenge to cultural-linguistic theory. Horizons: The Journal of the College Theology Society, 36(2), 215-234.